I believe that ALL students can and should learn deeply and joyfully every single day. (I also believe that everyone should find great joy–daily–in their work, but that’s for another post.)

So, what is Deep and Joyful learning, anyway? Sometimes when I wonder whether or not I should use the phrase. In particular, I worry that the “joyful” part sounds fluffy–that it sounds like I care more about superficial happiness than I do about rigorous learning. But nothing could be farther from the truth.

I liken deep and joyful learning to the way you feel after a really great run or a spin class or game of soccer. You know, how you give it everything you have, you dig deep, and you end both exhausted and elated.

It’s like that.

You see this in classrooms regularly. Students are buzzing with enthusiasm as they solve problems, make new meaning or transfer their learning in one area to another. I ask you, is this happening for all students every day in your school? If we’re truthful with ourselves, probably not.

Even setting that expectation probably feels overwhelming. After all, teachers have so many standards to cover and their jobs are so complex, that to ask them to make sure each student is joyfully learning seems like a huge ask. And sure, as with any goal, we set ALL or 100% of students as an aspiration–knowing that the higher we set our targets and expectations, the better chance we have at getting better results.

OK, but HOW do we do this. From what I’ve observed, it’s all about regularly and repeatedly using a few high leverage strategies that allow students to develop multiple competencies simultaneously.

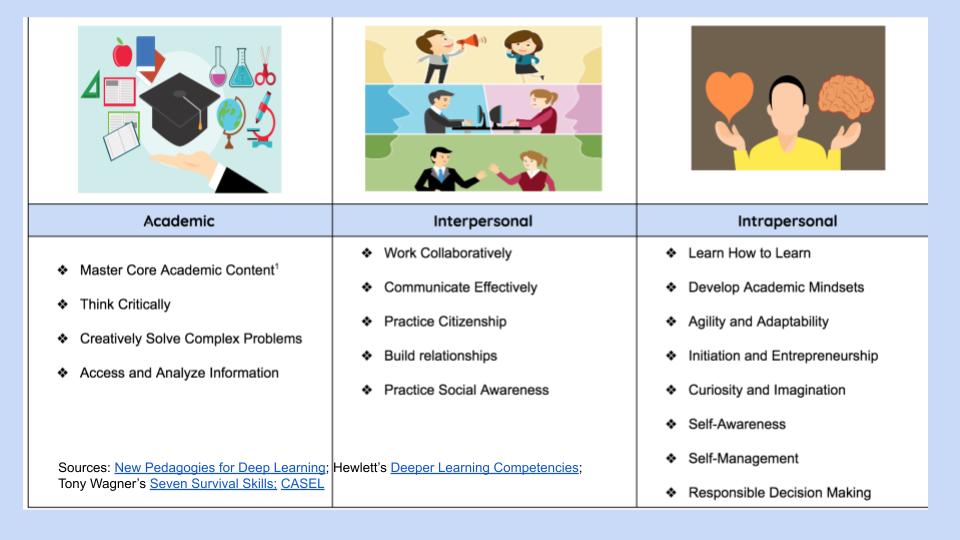

In synthesizing the work of Michael Fullan, Monica Martinez and the Hewlett Foundation, CASEL, and Tony Wagner, three distinct competency areas emerge:

- Academic–skills like critical thinking and complex problem-solving built around standards

- Interpersonal –skills like collaboration and communication

- Intrapersonal–skills like self-awareness and self–management and the ability to set and achieve goals and learn from mistakes.

In subsequent posts, I’ll go deeper into the importance of each area and share some strategies for developing them in and alongside our learners.

Read More

In 2013, Cuban and Tyack wrote Inside the Black Box of Classroom Practice: Change without Reform in American Education. In the book, they assert that even significant educational policy changes have largely left classroom practices untouched.

In 2013, Cuban and Tyack wrote Inside the Black Box of Classroom Practice: Change without Reform in American Education. In the book, they assert that even significant educational policy changes have largely left classroom practices untouched.

Few educators would argue with that thesis. Part of the issue is that the practice of teaching is largely a solitary one. Even schools that have embraced collaborative practices such as Professional Learning Communities or Instructional Rounds still have rooms of 1 teacher to 25 students, with doors that shut out the rest of the world.

Enter Covid and the move to remote learning, however, and suddenly the doors were opened wide. In this case, though, it wasn’t other teachers peering in, but parents and caregivers. And, as we know, that didn’t always go so well. Parents were often frustrated by unfamiliar material and teaching practices and felt both overwhelmed and helpless. Perhaps partly as a result of this, we saw a push from parents to get their children back in school as fully and quickly as possible. One almost gets the sense that parents were thinking–”I don’t care what you do with them all day, just don’t make me do it.”

This is unfortunate and represents a consistently missed opportunity. Of course, we should not expect parents to take on the role of teacher, but we’ve also done a disservice over the years by keeping instructional practices inside a black box–so much so that when it was forced open, many parents had a tough time deciphering the contents.

So what can we do to promote greater transparency (and with that, greater student engagement–the focus of an upcoming post).

Here are a few steps:

1. Every single course has a “course overview” to be shared with parents at the beginning of the year and referenced frequently.

As I’ve written in earlier posts, if we want to build student ownership of learning, school should be a series of surprises. Instead, we can let students know what they will learn, why they will learn it and how they might demonstrate their learning. A Course Overview does this by listing the power standards for each course and describing the types of typical learning activities and assessments to be used in the course. From there, teachers can invite student participation in co-creating the learning, but the overview provides a clear and coherent frame for the course.

Similarly, parents can review the overview and ask questions about it during discussions (perhaps during virtual open houses and/or during the events described below).

2. Schools run frequent, interactive “curriculum” or “teaching and learning” events for parents.

Because everyone went to school, most assume that they understand what’s happening. But both content and pedagogy have changed over time. Math, in particular, is likely to be unfamiliar to many parents.

Not only does the Algebra course my son took in 2015 look very different from the Algebra I struggled through in 1984, but elementary math instruction has also changed considerably. For one thing, there is considerably more focus, from an early age, on real world problem-solving that goes beyond the word problems of yore. There’s also a recognition that we need to allow students to engage in “productive struggle” in order to deeply engage with mathematics.

But parent comments like “The teacher doesn’t teach! My kids tell me they have to do all the work” tell me that we haven’t shared with parents the why behind any pedagogical changes.

We could use in-person or online “teaching and learning” events to showcase new approaches, perhaps using a shared text like Jo Boaler’s Mathematical Mindsets, for example. Parents, teachers and students could collaborate on rich problems together, gaining a mutual appreciation for new ways of learning.

3. Institute (student-led) digital conferences in place of the traditional parent/teacher conferences.

Covid has forced us to embrace new ways of communicating, and the move to online conferences might be one of the best changes worth sustaining. Rather than rushed 20 minute sessions with adults sitting in student desks, we can move to a more relaxed online setting that allows for greater flexibility for teachers and for working parents.

Using the course overview and student artifacts as a guide, parents and teacher can engage in a deep discussion about the child’s strengths and opportunity areas. If possible, having the student lead the conversation in terms of their own mastery of standards and competencies and explaining how they plan to proceed in the course is the best way to expand ownership. Then, if the parents and teachers feel the need for an adults-only conversation, they can arrange that as well.

Covid has broken down some of the walls between school and home. Let’s build upon that so that parents and teachers are true partners in the work of engaging and educating students.

Read More

Shhhhh. Finger raised to lips, teacher looks sternly at students. Once again, “sshsh:

Why?

What message are we sending our students when we shush them?

I recently posed this to some teachers I was working with. I’d noticed it in their classrooms and in others the day before. Now I couldn’t help but hear it.

And I cringed every time.

Look, I’ve done it. We all have. But when have to ask ourselves—what’s happening in a class that leads to the shushing?

Are kids talking “out of turn”? If so, why?

Are they trying to get clarification from another student? If so, why?

Are they shouting out the answer? If so, why?

In the first example, let’s ask—when should they speak?

Why isn’t this the “right” time? When CAN they speak?

More importantly, what happens when kids talk?

They think.

They inquire

They communicate

They make sense of things.

And when we shush, we shut that all down. We reinforce compliance and we make it clear who the class belongs to.

Shushing—that thing that we have ALL done at some point or another—likely means that we haven’t established a classroom in which students’ voice matters, in which they can engage with each other and with the teacher.

Let’s stop shushing and start creating robust classrooms full of meaningful dialogue and chatter. That’s when we think. That’s when we learn.

Read More