I believe that ALL students can and should learn deeply and joyfully every single day. (I also believe that everyone should find great joy–daily–in their work, but that’s for another post.)

So, what is Deep and Joyful learning, anyway? Sometimes when I wonder whether or not I should use the phrase. In particular, I worry that the “joyful” part sounds fluffy–that it sounds like I care more about superficial happiness than I do about rigorous learning. But nothing could be farther from the truth.

I liken deep and joyful learning to the way you feel after a really great run or a spin class or game of soccer. You know, how you give it everything you have, you dig deep, and you end both exhausted and elated.

It’s like that.

You see this in classrooms regularly. Students are buzzing with enthusiasm as they solve problems, make new meaning or transfer their learning in one area to another. I ask you, is this happening for all students every day in your school? If we’re truthful with ourselves, probably not.

Even setting that expectation probably feels overwhelming. After all, teachers have so many standards to cover and their jobs are so complex, that to ask them to make sure each student is joyfully learning seems like a huge ask. And sure, as with any goal, we set ALL or 100% of students as an aspiration–knowing that the higher we set our targets and expectations, the better chance we have at getting better results.

OK, but HOW do we do this. From what I’ve observed, it’s all about regularly and repeatedly using a few high leverage strategies that allow students to develop multiple competencies simultaneously.

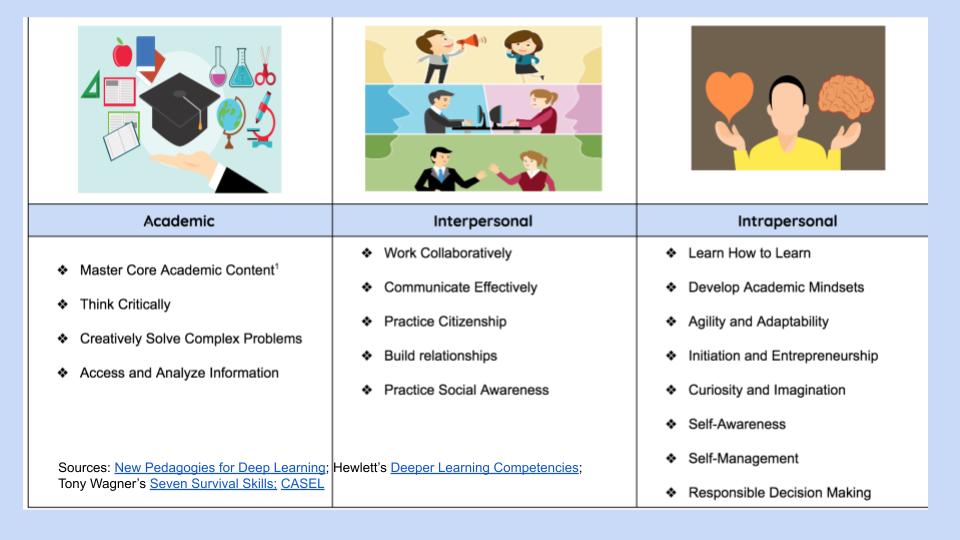

In synthesizing the work of Michael Fullan, Monica Martinez and the Hewlett Foundation, CASEL, and Tony Wagner, three distinct competency areas emerge:

- Academic–skills like critical thinking and complex problem-solving built around standards

- Interpersonal –skills like collaboration and communication

- Intrapersonal–skills like self-awareness and self–management and the ability to set and achieve goals and learn from mistakes.

In subsequent posts, I’ll go deeper into the importance of each area and share some strategies for developing them in and alongside our learners.

Read More

Teachers are overwhelmed. Parents are overwhelmed. Leaders are overwhelmed.

And, to be fair, this feeling isn’t new for educators, though it’s magnified now.

It’s time to simplify.

Simple does not mean easy. Simple does not mean that we are letting up on learning.

Instead, when we simplify, we arrive at what’s really essential.

When I’ve worked with curriculum teams, we usually start with the work of DuFour, et. al.

Here are their “big questions” to guide teaching and learning.

- What do we want all students to know and be able to do?

- How will we know if they’ve learned it?

- How will we support students when they struggle?

- How will we enrich the learning for students who are already proficient?

Educators always love these questions.

Great, I say. So, now, let’s answer that first question.

Teachers pull out their state standards, textbooks, final exams, etc and soon our response to question 1 fills up pages.

It becomes clear that we cannot teach everything if we want students to learn deeply and joyfully.

We need to strip down to the essential standards.

Teachers understandably have trouble with this. EVERYTHING feels essential.

But then I ask them to picture a capable student in their class. Now, consider that this student will endure some tough circumstances this year–perhaps illness–that causes him/her to be out for a significant portion of the year.

Most teachers can’t conceive of having this student repeat an entire year or course. So they then consider what the student would REALLY need to know and be able to do in order to move beyond this class or course.

We use this guidance from Larry Ainsworth to choose our essential standards (aka Power or Priority Standards.)

Essential standards are those that exhibit:

- Endurance–skills and knowledge needed for life outside this course

- Leverage–skills and knowledge from this course that help us learn and understand standards in other courses

- Readiness–skills and knowledge that we must have to advance to the next year/course

In fact, there are schools and teachers that do this regularly for students with special circumstances.

We just never considered that we would need to do this for all students…in all subjects.

But we can. Simplify. Get down to the essentials–the real and true essentials and go from there.

Right now, I would ask teachers to consider the ONE thing students must know or be able to do between now and next year. How can we teach that? How will we (and students) know if they’ve learned it?

Then, go on to prioritize the NEXT thing on the list and so on. If the first is all we can reasonably achieve this year, so be it.

Kudos to those districts that have made this focus on essential standards crystal clear, reducing overwhelm and giving space for deep and joyful learning.

#ourFCPS friends- Essential Standards for remaining instructional weeks for ES & MS are posted to Distance Learning Support (teacher-facing) BB site. For ES, also posted to ECF google site at https://t.co/LauP8aXIwm (FCPS google log-in required). @kmkoelsch @christiepday pic.twitter.com/uP74XXrrLp

— Andrea Hand (@AndreaHand2) April 12, 2020

Read More

Shhhhh. Finger raised to lips, teacher looks sternly at students. Once again, “sshsh:

Why?

What message are we sending our students when we shush them?

I recently posed this to some teachers I was working with. I’d noticed it in their classrooms and in others the day before. Now I couldn’t help but hear it.

And I cringed every time.

Look, I’ve done it. We all have. But when have to ask ourselves—what’s happening in a class that leads to the shushing?

Are kids talking “out of turn”? If so, why?

Are they trying to get clarification from another student? If so, why?

Are they shouting out the answer? If so, why?

In the first example, let’s ask—when should they speak?

Why isn’t this the “right” time? When CAN they speak?

More importantly, what happens when kids talk?

They think.

They inquire

They communicate

They make sense of things.

And when we shush, we shut that all down. We reinforce compliance and we make it clear who the class belongs to.

Shushing—that thing that we have ALL done at some point or another—likely means that we haven’t established a classroom in which students’ voice matters, in which they can engage with each other and with the teacher.

Let’s stop shushing and start creating robust classrooms full of meaningful dialogue and chatter. That’s when we think. That’s when we learn.

Read MoreDifferentiating learning for all students is hard enough—now we are asked to think about giving students a choice and voice in their own learning. Seems like more work for the teacher. And, on the front end, it is.

But here are some ways to make it easier.

1) Give students choice in a JIGSAW. Usually, jigsaws are used by teachers looking to differentiate learning for their students. The teacher chooses 3 or more materials related to the topic of discussion. The materials may differ according to reading level or interest or, sometimes, are simply a number of related resources that are valuable, but there are just too many to have each student read each one, so using a jigsaw allows students to get summaries from their peers.

You can also do this with a flipped Jigsaw—in which the students read or view (in the case of a video, etc) their chosen piece at home, take notes and prepare a summary to share with their peers the next day.

2) Then, allow students some choice in how they create a product to share with their peers. Usually, after a jigsaw, I’ve provided a choice board— a menu of activities the group can do to make synthesize their learning. This is great. It gives the group a choice and, done well, teaches students how to make group decisions and then work together. (See examples of choice boards here and here)

But you could do this differently. You could do the meaning making part of the jigsaw in class. Students either read and create summaries in their home group in class or they’ve done some of this work at home in the flipped scenario, and then come together briefly to create a group summary to bring to their rainbow groups. Then, have the rainbow groups come together for discussion of all the readings/resources and make sense of them tougher, engaging in dialogue and debate (structured or unstructured based on their familiarity with the process, age, your preference, etc). After that, instead of working on group projects for the final piece, students might choose to work individually—or some might work in pairs, or you might have a sign up sheet (physical or on a shared document) where students sign up for the type of final product they want to create. So, you might end up with 3 groups of 4 students who want to create a game based on the readings and 2 students working individually to write a poem and others doing any number of appropriate learning tasks. (Note that the options in the choice board should have accompanying rubrics whenever possible in order to ensure rigor).

Finally, I would recommend bringing the class together for presentations (OR having the students make videos of their presentations for their peers to watch at home) and including some sort of feedback sheet from peers. (More on that to come).

One last thing—I don’t think it’s possible to overuse the Jigsaw. If you are new to differentiation, ad/or if you find it incredibly time-consuming, why not return again and again to something that works. You can mix up HOW you assign pieces or give choice, you can mix up the activities or questions in the home group and the rainbow group, you can have students do the final product in groups or individually. The final products can take hours or weeks or days. I would love to see examples from others.

Read More